[Bangor Daily News] Portland photography shows connect Maine immigrants to mid-century Africa

[Bangor Daily News] Portland photography shows connect Maine immigrants to mid-century Africa

By TROY R. BENNETT

Friday, March 31th, 2023

Click HERE to view full article

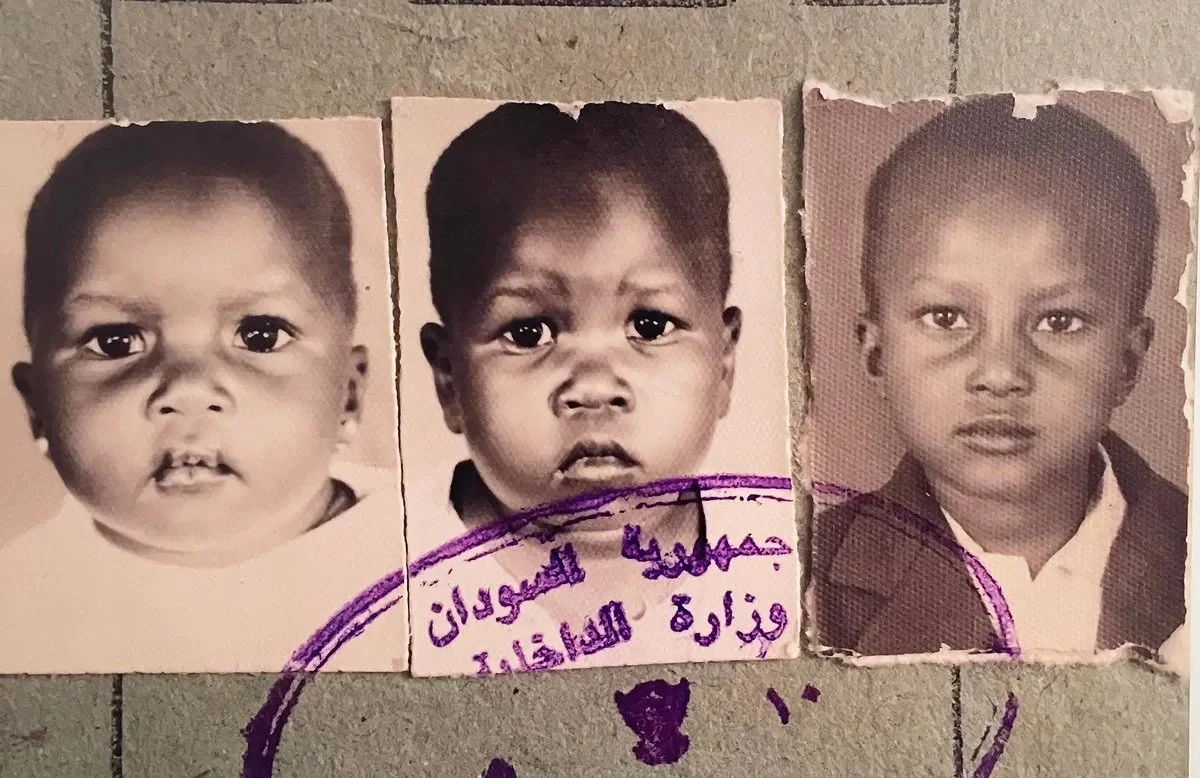

Elizabeth, Anna and Lazarus Donato's pictures are stapled to the emergency transit documents their grandmother used to take the family from Sudan to Maine in the 1990s. The images are part of a photo show at the Portland Public Library organized by the Greater Portland Immigrant Welcome Center. Credit: Courtesy of Elizabeth Donato

PORTLAND, Maine — Photographer Todd Webb spent five months in 1958 making pictures for a special United Nations project, illustrating technological and industrial advances in nine African countries.

Webb, who eventually established his home and official archive in Maine, made nearly 2,000 images for the U.N. report. Most of the pictures were in rapturous, revelatory color, which was still a rarity at the time.

However, the international agency only published 22 of Webb’s pictures, in a single, unremarkable, black-and-white brochure. The rest of the photos went into storage, unseen by the public and largely forgotten.

Until now.

The Portland Museum of Art, the Todd Webb Archive and the Minneapolis Institute of Art are currently presenting Outside the Frame: Todd Webb in Africa, which features dozens of new prints made from Webb’s 1958 negatives.

It’s on view at the Portland Museum of Art until June 18.

The photos provide a glimpse of life on the continent just before a number of its countries separated from their European colonizers. Meant to illustrate progress at the time, Webb’s pictures now seem to show a land still fully under the thumb of white outsiders bent on extracting as much natural resource wealth from Africa’s seas, forests and underground oil reserves, before their total rule ebbed away.

Webb, who died in 2000, in Lewiston, at the age of 94, was a progressive of his time. He steered clear of over-exoticising subjects but, given his western background, couldn’t help but shoot from a white, outsider’s perspective.

Two images Maine photographer Todd Webb made in Africa while on assignment for the United Nations in 1958: At right, a Togolese man stands at an American-style gas station. At left, a man applies pesticides to a cocoa crop in Ghana. Credit: Courtesy of the Portland Museum of Art

To even out the show’s viewpoint, the museum is also presenting a companion show at the Portland Public Library. Co-organized with the help of the Greater Portland Immigrant Welcome Center, it features photographs curated by Mainer’s who used to call Africa home.

The Immigrant Welcome Center is hosting a reception at the library with African snacks, music and dancing on Friday, April 7, from 5 to 7 p.m. It will also present a pair of community conversations featuring African immigrants recounting their personal and family stories on Friday, May 5 and Friday, June 2. Both events start at 6 p.m.

“Although Webb’s images are beautiful,” said Bau Graves. “They were taken at a time before most African countries had gained their independence, and before the civil wars that displaced so many people.”

Graves is the development officer at the Immigrant Welcome Center and served on the special advisory panel which helped assemble the library show.

“Because of those wars, we have a sizable community of Africans right here in Maine,” Graves said. “Many of them have pictures of their families, loved ones and their communities back in African countries.”

The museum and library sets of images, though connected by the same enormous continent, couldn’t look more different from one another on the surface.

Webb’s photos, at the museum, are the bold, sleek, well-composed work of a seasoned artist and professional. The Immigrant Welcome Center’s show, at the library, is made up of mostly faded, blurry snapshot images.

But both sets of photos are suffused with deeper meanings and inform each other.

In service to his mission at the time, many of Webb’s pictures illustrate grand industry. In one image, giant logs are loaded onto a ship. In another, 10 men push a cart laden with dozens of wooden barrels on a seaside dock.

In one of Webb’s most striking photographs, a Togolese man in coveralls stands at an American-style Texaco gas station, nozzle in hand, ready to serve, as the white photographer’s camera lens gazes at him.

“The photo expresses both the shiny capitalism and the inequities of the 1950s, even as celebrations of independence took place on nearby streets,” reads a caption beside the framed picture.

Once a colonial slave-trading hub, Togo gained its full independence from France in 1960.

Other Webb photos show tobacco growers auctioning their crop to Americans, miners caked in dust and a man blowing a cloud of pesticide on cocoa crops. Each image is arresting, both for the photographer’s mastery of his medium but also for his pictures’ shifting, evolving meanings over the ensuing 60-plus years.

In contrast, the images at the library are all family photos. Some are cherished family heirlooms, while others are more recent.

One picture shows Mainer Lydianna Lubwini fording a stream with her sister Bocala Kundomba on the Panama-Colombia border last year as they made their way to the United States. One woman wears a backpack and carries a gallon jug of water. The other balances a garbage bag of belongings on her head while leaning on a foraged walking stick.

Both women look hopeful and manage slight smiles.

By artistic standards, the picture En’kul Kanaken donated to the show, doesn’t rate very high. But what it lacks in quality, it more than makes for in sentiment.

The photo shows Kanaken’s young son, Michael, as a toddler, reaching far above his head to beat on a traditional Burundian drum at a festival.

“He was about 18 or 20 months old,” Kanaken said. “He was very, very, very active because he started walking at seven months. He was a happy child growing up and I just remember those happy moments. They were the times before. Later on, when he was a little bit older, maybe five or six, we started having a lot of trouble in Burundi.”

It was that trouble which brought the family to Maine.

Mainer Elizabeth Donato donated a series of three photos to the exhibition. They show her and her two brothers as young children. The trio of headshots was stapled to their official United Nations High Council on Refugees emergency travel documents.

Donato’s grandmother carried the documents when she left Sudan with her three grandchildren in 1997.

“My grandmother, she keeps literally every document. I think it might just be an in general immigrant thing,” Donato said. “My mother was not alive and my father wasn’t in the picture. So she was really the sole caregiver. It was really difficult for my grandmother but I think something that rings true for me about all immigrants is that they’re resilient and really wanting to have a better life for them and their children.”